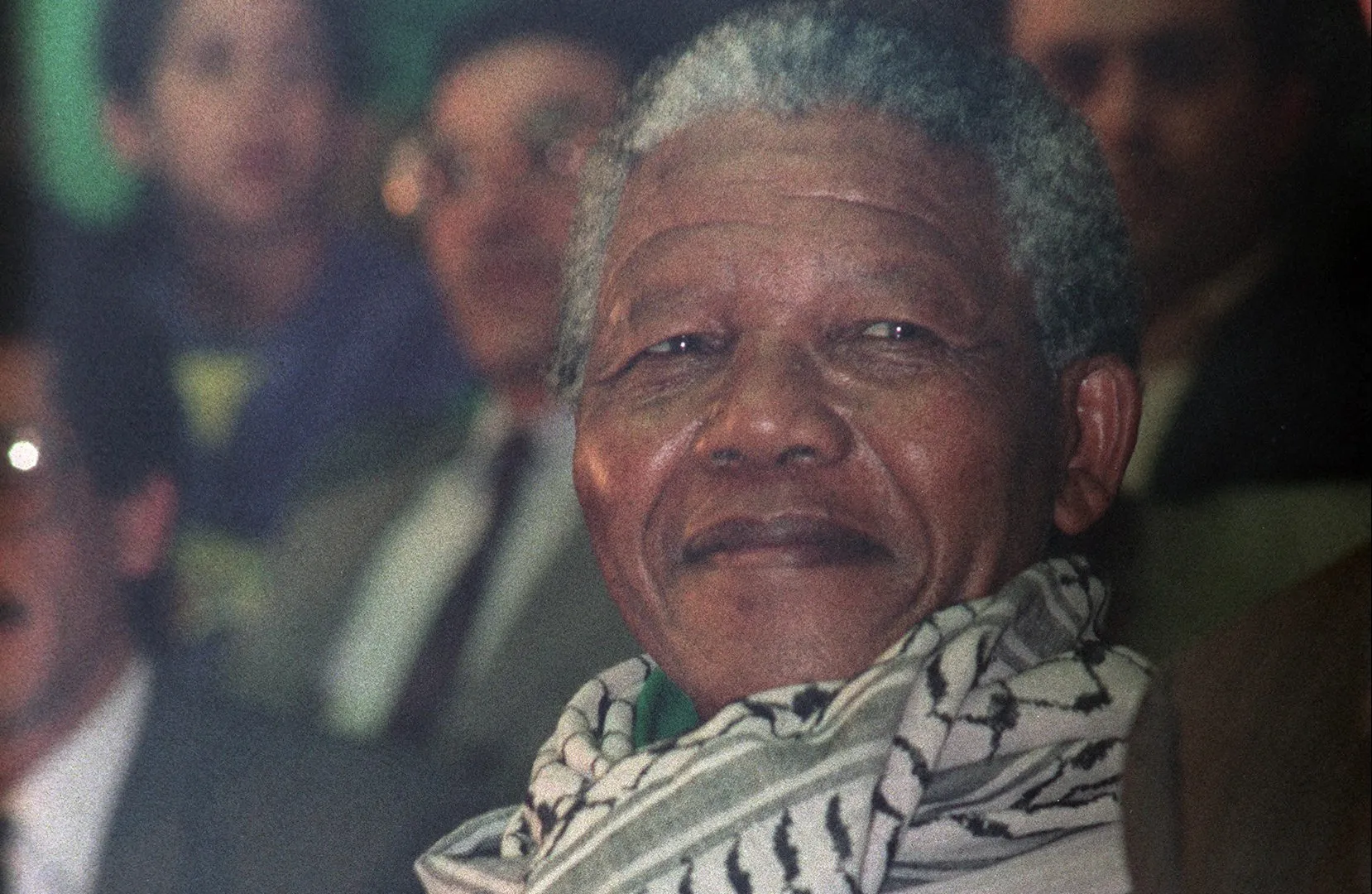

“It is said that no one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails”

Nelson Mandela

On Mandela Day, it is important to reflect on his legacy. What has changed since apartheid ended in South Africa and what lessons do we have for the world? In what ways have we fallen short?

The mass incarceration of political prisoners was one of the hallmarks of apartheid in South Africa. Many were held in administrative detention – that is without trial or even being charged. Likewise in Palestine, mass incarceration has been used by Israel as a political tool for decades.

The overt goal of mass incarceration is to suppress resistance. But there is an even more sinister reason that apartheid systems use this tactic. One with consequences that persist even when a transition to democracy eventually occurs.

Understanding the role of mass incarceration in entrenching apartheid is critical in the fight for Palestinian freedom. It can also help us work towards the systemic change necessary in South Africa’s prison system in 2024.

The Impact of Imprisonment on Identity

The recent death of Walid Daqqa brought renewed attention to Israel’s systematic incarceration of Palestinians in Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza. Daqqa was one of the longest serving political prisoners in Israeli jails. The conditions of both his life and death in captivity have helped shed light on the inhumane human rights abuses enabled by Israel’s ‘criminal justice system.’

But there is no better way to understand why Israel incarcerates so many Palestinians than through Daqqa’s own words.

Having dedicated much of his time in prison to writing essays and stories, Daqqa developed the idea of how the ‘little prison’ in which he spent most of his life paralleled the ‘big prison’ of the territories occupied in 1967, in which the freedom of millions of Palestinians is severely restricted.

The goal of such overarching suppression is not to secure Israeli Jews against armed resistance of organised groups. Its aim even goes beyond crushing non-violent resistance. Rather, it is an attempt to prevent Palestinians from considering resistance as an option in the first place.

In doing so, it further aims to fragment the Palestinian collective, dissolving Palestinian consciousness and remaking their identity as docile people resigned to living in perpetual statelessness.

Within Palestinian society, the attempt failed. The evolution of Palestinian identity has been impacted by occupation, but not in the way Israel had hoped. The Palestinian people have never stopped persevering in the fight for liberation.

However, through their campaign to criminalise Palestinian existence, Israel has created a dehumanising framework for how people in Western nations see Palestinians.

The Dehumanising Power of Imprisonment

There is no more poignant indication of the success of this tactic of dehumanisation than the Western world’s focus on death tolls in Gaza. When they criticise Israel, it is for the high rate of civilian deaths. They measure destruction only in terms of lives lost.

The obliteration of homes, possessions, businesses, family life, and dreams and aspirations is not mentioned by Western leaders or mainstream media outlets. Compare this to the discourse surrounding lockdowns in 2020, when many of these same mouthpieces expressed their openness to risking death rather than putting their economic and social lives on hold.

To some extent, the focus on death tolls can be viewed as a way of reducing Israel’s crimes to so-called collateral damage. However, it works because Palestinians have rarely been viewed as ‘real’ people by much of the world.

Even those of us advocating for Palestinian rights can fall into this trap when we speak about the West Bank and Gaza as ‘open-air prisons.’ We do so to shine a light on the ghetto system Israel has created but it can make people lose sight of the value of the lives of those who live there – after all, what do people who live in ‘open-air prisons’ have to lose?

This description belies the fact that people living under occupation have homes and communities, love lives, creative aspirations, and an ancestral connection to the land itself.

It also points to a fundamental mistake we make when thinking about people in prisons. The constraints of incarceration do not suppress a person’s internal life. Often, the contrary is true.

Walid Daqqa’s Life in Prison

Thousands of Palestinians, including hundreds of children, are arrested each year by Israeli forces and held in detention for months without charge. Those who are charged are tried in military court proceedings that take place in Hebrew, without a translator being provided.

They are denied legal representation, making it a near-certainty that they will be found guilty. Many are tortured until they confess or are driven to confess by the threat of neverending detention if they don’t.

Walid Daqqa was a Palestinian citizen of Israel and a member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). In 1986 he was charged with supposedly leading a group that killed an Israeli soldier. He had an airtight alibi for the incident itself and there was very little evidence to substantiate the charge.

In order to impose a particularly severe sentence on him, Israel implemented outdated British emergency regulations that allowed them to lower the standard of proof required for conviction. He was given a life sentence, which was reduced to 37 years in 2012.

During his almost four decades of imprisonment, he was subjected to extended periods of solitary confinement, physical and psychological torture, and medical neglect. He was often denied regular visitation rights.

A revolutionary act against ethnic cleansing

Daqqa got married in 1999 but Israel imposed a blanket ban on conjugal visits. Still, he managed to conceive a child with his wife by smuggling sperm out of prison. This common form of resistance is a revolutionary act against the ethnic cleansing tactics of the Zionist regime.

He met his daughter Milad (now four years old) only once before his death.

In spite of the suffering Israel put him through in an attempt to break him, he achieved remarkable things during his years behind bars, with his writing gaining widespread recognition and respect in Palestine and around the world.

In his final years, he was denied adequate medical treatment for leukaemia and myelofibrosis. Appeals for compassionate release were rejected – instead, his sentence was extended for two years for allegedly smuggling cell phones.

After October 7, his treatment by the Israeli prison system became significantly worse. He was denied adequate food and was being subjected to savage beatings even as he lay dying. He was further denied the opportunity to say goodbye to his wife and daughter.

Israeli authorities refused to release his body to his family for burial, extending his thirty-eight years of imprisonment even beyond his death.

The story of Daqqa’s imprisonment, while harrowing, is not unique. Thousands of Palestinians have been as badly abused in prisons, with children no exception to horrific treatment.

Palestinians in Captivity (in Numbers)

Pre-October 7

Approximately 5,000 Palestinians were held in Israeli prisons pre-October 7, 2023, including 160 children. One in five Palestinians in the West Bank have been held in Israeli prisons. This number rises to two in five for Palestinian men.

Administrative Detention: Over 1,100 (22%) of those held pre-October 7 were in administrative detention, a practice that allows indefinite detention without charge based on ‘secret information’ not provided to the detainees or human rights organisations.

Conviction Rates: Israeli military courts convict over 99% of Palestinians brought before them. Many detainees accept plea bargains in order to avoid prolonged pretrial detention with the understanding that they will almost certainly be found guilty.

Conditions and Treatment: For decades, released prisoners have reported severe mistreatment, including torture, sexual assault, lack of clean water, inadequate food, and medical neglect.

Child Detainees: Hundreds of Palestinian children are arrested each year, often based on unfounded allegations of stone-throwing, including against armed and armoured soldiers and tanks. Released children report the trauma of nighttime arrests and interrogations without guardians, prolonged detentions, solitary confinement, beatings, and sexual assault.

Post-October 7

The number of Palestinians arrested in the West Bank and East Jerusalem has risen dramatically since October 7, 2023. As of July 2024, approximately 10,000 Palestinians from the West Bank are being held. Over 2,000 are in administrative detention without charge.

Thousands of people in Gaza have also been abducted by Israeli forces and held in torture camps such as Sde Teiman.

Administrative Detention: Over 3,600 (36%) of those held as of April 2024 are in administrative detention.

Conditions and Treatment: Released detainees from the West Bank have reported a significant increase in the severity and regularity of beatings and other forms of mistreatment, as well as the withholding of food, water, and medication. The overcrowding of these prisons has contributed to increased neglect and worsening hygiene.

Post-October 7, 2023

Doctors in a Torture Camp

Dr Mohammed Abu Salmiya dedicated himself to healing the people of Gaza as the head of Al Shifa Hospital, even as it was bombed and besieged by Israeli forces. He was tortured In the camp where he was held for seven months. The overseers of this treatment: doctors too, dystopian counterparts to his profession who enact rather than prevent premature death.

Multiple detainees have died, including other medical personnel taken captive from Al Shifa. Many more have suffered permanent injury, including amputations due to the inhumane conditions.

Testimony from witnesses, including Dr Abu Salmiya, detainees and Israeli whistle blowers has consistently included the description of such tortures as electrocution, denial of sleep, and violent sexual assault, such as the rape of captives with metal sticks.

Dr Abu Salmiya was arrested after Israel claimed without evidence that Al Shifa hospital served as a base for Hamas’s armed wing. He was released at the beginning of July due to a lack of space in the torture camp.

Gaza Torture Camp

Released detainees and Israeli whistleblowers have exposed many inhumane practices at Sde Teiman, a camp where Israeli forces take captives from Gaza. Captives are left blindfolded for months. The extended use of cable ties to bind wrists has led to multiple amputations. Doctors – including many designated as such who have had no medical training – have participated in torturing captives.

Torture has included electrocution, denial of sleep, and violent sexual assault, such as the rape of captives with metal sticks.

People released after months of torture have returned to Gaza having lost an average of 30 pounds (13 kilograms). Some have remained unable to speak for weeks after release, due to the extent of the trauma they suffered.

It is unknown how many people are held in Israeli torture camps at present as Israel provides no information to organisations or families. It is also unclear how many have died from beatings and inhumane conditions.

Palestinian Citizens of Israel

Bayan Khatib is a 21-year-old engineering student. She is also a Palestinian citizen of Israel. In October last year, she posted an Instagram story that showed shakshuka being prepared, with the words ‘We will soon be eating the victory shakshuka’.

She was harassed by Israeli students, dismissed from university, fired from two jobs, and later arrested and held for three days without charge in three different prisons.

In an interview with PBS reporter Leila Molana-Allen, she described conditions of overcrowding and the intentional humiliation of Palestinian citizens of Israel detained. Some of the women had their hijabs confiscated and were made to wear garbage bags on their heads.

Israeli claims that the state is a free democracy with equal rights hinge on the existence of Palestinian citizens of Israel. This has always been a misrepresentation at best, with dozens of laws that discriminate against Palestinian citizens of Israel, as well as racist policing and the underfunding of Palestinian cities and schools.

However, since the 7th of October, conditions have become far more oppressive for Palestinian citizens of Israel. While Bayan Khatib was arrested for an innocuous social media post, many others have been arrested for even less – ‘crimes’ such as liking social media posts supporting Gaza and being part of Whatsapp groups where Gaza news is shared.

In many of the more than 160 arrests related to alleged ‘speech-related’ offences, the process has been brutal and incarceration has extended for weeks or months.

Prisons in Post-Apartheid South Africa

These stories are horrific, but because the detained Palestinians are labelled as prisoners rather than hostages, many around the world remain unmoved.

Unfortunately, this is a reality of prison systems around the world. Prisoners are the least likely segment of any population to receive sympathetic media coverage. Which is why conditions in prisons often remain unchanged even when systems of oppression officially come to an end.

The legacy of apartheid has led to lasting problems in a democratic South Africa. It is impossible to ignore the mass poverty, hunger, and violence that plagues the most vulnerable.

However, the issue of prisons in post-Apartheid South Africa is often overlooked, despite enabling some of the worst human rights abuses in the country today. South Africa has the biggest prison population in Africa and conditions of ‘overcrowding; poor ventilation; inadequate ablution facilities; violence; lack of sanitation and privacy; a shortage of beds and bedding; insufficient supervision and oversight; and poor healthcare provision’ have led to detainees living in inhumane conditions.

Out of the more than 161,000 people held in prisons, over 43,000 are in remand – awaiting trial or sentencing. In other words, some have still not been found guilty of a crime while others may end up serving longer sentences than appropriate for the crime they committed. In many cases, it is an inability to afford bail that leads to long periods of remand rather than the severity of the alleged crime.

The discriminatory nature of South Africa’s prison system is even starker for asylum seekers. Since the end of last year, arrests of asylum seekers took place at refugee offices before they had the chance to be interviewed on the merits of their appeal for refugee status, leading to their detainment in inhumane conditions and potential deportation.

It seems these arrests are stopping but many challenges remain, including a lack of access to protection from the asylum system. With appointments being scheduled for dates between 2025 to 2027, asylum seekers remain undocumented and vulnerable to arrest.

Advocacy groups continue to push back at the ongoing regressive changes to the asylum system.

Prison systems perpetuate inequality

Prison systems are unequal around the world. People struggling economically are more likely to commit a crime in the first place in order to meet basic needs. Legal systems are not neutral, and often work hand in hand with the carceral system to criminalise certain ‘undesirable’ bodies.

Globally, especially in (‘post’) colony societies, those criminalised constitute historically disenfranchised groups, targets of white supremacy and the poor. These groups are profiled by enforcement bodies, disproportionately represented in prisons, and may be financially excluded from recourse to protection through bail and adequate legal representation.

In countries which were subjected to colonial systems, the legacy of past abuses remains and prisoners suffer for it long after oppressive laws are abolished.

The Shared Fight for Freedom

In fighting apartheid in Palestine, the world looks to South Africa for guidance in facilitating a transition to democracy. It’s crucial that lessons are taken from our mistakes as well.

The extent of the abuses committed by Israel against Palestinians can also provide lessons for South Africa. It provides a vivid reminder of how incarceration is used as a tool of dehumanisation, giving us the chance to reconsider how we perceive people in our own prisons so that we can advocate for them.

Decolonisation is a process that requires us to dismantle the very systems used to entrench inequality.

Organisations advocating for the rights of Palestinians held in prisons by Israel include samidoun and Defense for Children Palestine.

Organisations advocating for the rights of South Africans held in prisons include Southern African Network of Prisons (SANOP), Sonke Gender Justice, and SaferSpaces.

Scalabrini is advocating for the rights of asylum seekers and against practices that put them at risk of arrest.

Sources

- https://www.saferspaces.org.za/understand/entry/prison-violence-in-south-africa-context-prevention-and-response

- https://thepublicsource.org/parallel-time-walid-daqqa

- https://mondoweiss.net/2024/04/the-palestine-walid-saw-from-the-little-prison-to-the-big-prison/

- https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/04/israel-opt-death-in-custody-of-walid-daqqah-is-cruel-reminder-of-israels-disregard-for-palestinians-right-to-life/

- https://www.aljazeera.com/program/newsfeed/2024/7/1/al-shifa-hospital-director-held-by-israel-and-beaten-for-months-now-free

- https://www.bmj.com/content/386/bmj.q1524

- https://www.aljazeera.com/program/newsfeed/2024/7/1/al-shifa-hospital-director-held-by-israel-and-beaten-for-months-now-free

- https://www.adalah.org/en/content/view/10926

- https://www.trtworld.com/middle-east/sodomised-to-death-stories-of-torture-at-israels-sde-teiman-base-emerge-18170660

- https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/11/29/why-does-israel-have-so-many-palestinians-detention-and-available-swap

- https://law4palestine.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Law-for-Palestine-Report.-Israels-Arrest-Policy-against-Palestinian-University-Students-in-the-West-Bank-and-Israel-.pdf

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/4/17/palestinian-prisoners-day-how-many-palestinians-are-in-israeli-jails

- https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/palestinians-describe-harassment-from-israeli-forces-over-social-media-posts-during-war

- https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/israeli-police-release-palestinian-woman-after-arresting-her-for-post-about-rafah/3235920

- https://www.scalabrini.org.za/press-release-unlawful-arrests-of-new-asylum-seekers/